Understanding OCD

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder is more than what social media portrays

October 11, 2021

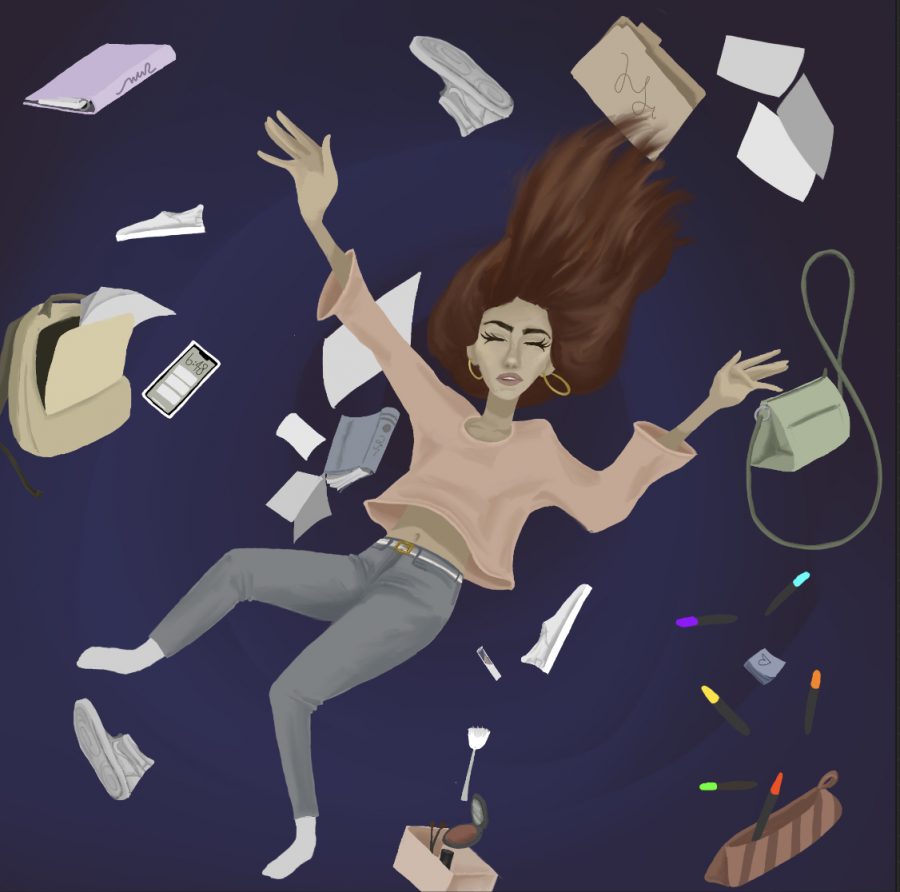

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder is a well-known mental disorder, but it is shrouded by misconceptions. This disorder affects individuals in many aspects of life.

The true definition of OCD can often be misconstrued. Senior Darby Allen, Wingspan’s design editor, was diagnosed with this disorder when she was 12.

“OCD is basically a flood of intrusive thoughts or the obsessions that cause you to do repeated motions that will quell those bad thoughts. But a lot of the times, these motions make them worse — this causes a vicious cycle,” Allen said.

OCD can affect every aspect of one’s life.

“It’s hard to be a teenager and carefree,” Allen said. “Teenagers do things and don’t think about it, but it’s hard for me to be spontaneous because, with every action I do, I overthink. It’s hard for me to have fun because of the fears I have and the actions I think I need to do. … I still find myself abstaining from certain activities because of my OCD.”

Mental disorders are often looked down upon simply because they’re misunderstood. This can be frustrating to those who are struggling.

“I think people need to understand that I don’t need to grow up — I’m not being a baby or a coward,” Allen said. “Just because I look at life differently doesn’t mean I’m inferior or I need to change. People need to understand it’s not my fault, and I’m not weak; I can do anything anyone else can do.”

Ryan Wilderman, a clinician at the International OCD Foundation in St. Louis, has been treating those diagnosed with OCD for more than five years.

OCD can manifest itself in various ways — the symptoms can vary from person to person.

“Some people become afraid that they will make mistakes and will completely avoid things like homework, going to school or sending texts until they can know it will be correct,” Wilderman said. “Other people have very complicated sets of compulsions and rituals that they feel they must do or else. Regardless of how OCD may be for each person, it is always an attempt for certainty — knowing for sure the bad thing won’t happen, knowing for sure that something is right and knowing for sure the awful feeling or thought will go away.”

Through the years, Allen said she has been able to see some of the positives that have come from her diagnosis.

“I’m very public about [OCD], and it warms my heart when people come up to me and say ‘Darby I’m starting to develop OCD and you talking about it really quelled my fears about it,’” Allen said. “While it is a very terrible disorder, and I wouldn’t wish it against my worst enemy, it has made me a stronger person.”

In the media, mental disorders can often be misrepresented, changing perceptions. OCD falls victim to this.

“I think it is tied to what we see in TV, movies and social media,” Wilderman said. “The stigma I see is more related to downplaying what a person experiencing OCD goes through and sets an expectation that the person ‘needs to stop it’ and they are ‘dramatic.’ There is also a stigma that OCD means overly clean and orderly. Unfortunately, this leads people experiencing OCD to label themselves as lazy or unmotivated because they cannot seem to get themselves to engage in tasks like chores or school work, even though they would actually like to. Many times, this stigma delays people from getting help or prevents it altogether because ‘I don’t have an issue, I’m just lazy.’”

There are ways for schools to help alleviate this stigma.

“First and foremost, helping educators and school counselors become more aware and comfortable with recognizing at-risk behaviors — like school avoidance or … school work — so that they can potentially direct the person to help,” Wilderman said. “Another way to assist with overall representation in schools is to take advantage of mental health month and provide information about OCD to students and what can be done to help.”

Nixa High School is taking steps to help normalize mental health struggles. Counselor Carrie Stormzand helped organize Awareness Day, held on Sept. 24, and a program called Sources of Strength. These programs have helped fight an arising mental health crisis.

“I’m hoping that we’ll take steps for improvement and that we’ll have … opportunities to bring new programs into the school,” Stormzand said. “With Sources of Strength being a preventative program, it’s important for us as a school to look at our students as a whole person and not compartmentalize academics. You can’t compartmentalize mental health or academics since they can affect each other. Every person has mental health just like physical health; it can be very much a parallel to our physical health.”

Counselors warn against Googling symptoms in an effort to self diagnose. This can be harmful to those struggling with metal health.

“One of my favorite lines is, ‘You’re always going to find what you’re looking for,’” Stormzand said. “If you think something’s wrong, you’re going to find info to back it up. If you do feel like something is not OK, or it’s anxiety related, and you are having intrusive thoughts or compulsions, reach out to a trusted adult or to qualified individuals who can give you a true diagnosis.”

Although cliché, there is always a light at the end of the tunnel.

“OCD is very difficult to deal with, but you can get through it, you can get through anything,” Allen said. “Stay strong, don’t give up, and don’t be afraid to ask for help. Everything is going to be OK.”