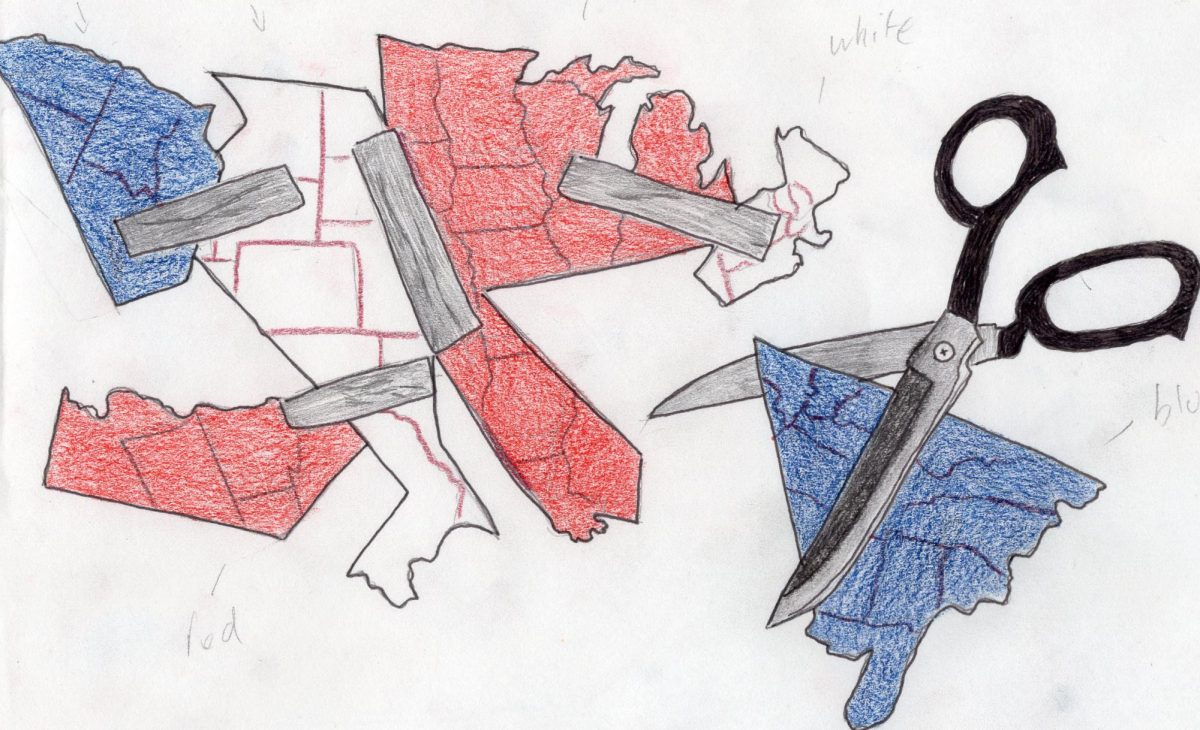

Diversity, equity and inclusion efforts gained new attention less than a week into President Donald Trump’s second term when he signed two executive orders reversing DEI policies. This decision led to some experts highlighting the importance of understanding historical events and how demographics and inclusion have changed over time. One such event is the 1906 lynchings in Park Central Square in Springfield, Missouri.

By the end of the 1820s, white settlers moved to Greene County, bringing enslaved people with them. This led to an influx in the Black population.

“By the time you get to the Civil War, Greene County is a little over 10 percent enslaved people,” Dr. Brooks Blevins, the Noel Boyd Professor of Ozarks Studies at Missouri State University, said. “So there was a larger Black [percentage] population then than there is now.”

During the Civil War, Springfield became a magnet for white and Black refugees from around the Ozarks. This led the Black population to increase during the Civil War and a couple of decades after.

“If you look at 1870, almost 20 percent of the population of Springfield was Black, and then it was almost 23 percent in 1880,” Blevins said.

This is a drastic difference compared to the statistic today, over a century later. According to the U.S. Census Bureau in 2023, only 4.3 percent of the population of Springfield was Black.

As more African Americans moved to Springfield, they began to gain political influence.

“They actually had a Black city councilman, Alf Adams,” Kimberly Harper, an editor at the State Historical Society of Missouri and author, said.

However, this newfound political influence did not last. In addition, the demographics of Greene County saw a large drop in the Black population. Historians debate what caused the shift, but there are two particular answers that tend to be referenced frequently.

First, by 1890, Greene County had faced rapid growth in its white population. This caused the white population to overtake the Black population, which led Springfield’s demographics to only be 10 percent Black by 1890. The trend continued for decades, causing the Black population to get even smaller and lose more political holding.

Second, the lynching of three Black men in Springfield’s Park Central Square instilled fear in the community, which may have shifted the demographics and the political scene.

In Harper’s book “White Man’s Heaven: The Lynching and Expulsion of Blacks in Southern Ozarks,” this pivotal event took place on the eve of Easter 1906. It all started with Mina Edwards, a married woman, and Charles Cooper, both white, who claimed they had been on a buggy ride together when two African American men stopped the two, robbed Cooper, and then assaulted Edwards.

“Shortly after he was robbed, Cooper identified [Horace] Duncan as one of his assailants,” Harper said. “Duncan and his coworker [Fred] Coker were taken into custody. After their employer vouched for them, they were released.”

In response to their release, Cooper made a public statement stating that Duncan and Coker were the men he and Edwards had gotten into an altercation with. The two men were promptly rearrested.

“The Springfield police chief and Greene County sheriff did not attempt to transport the men to a jail outside of town where they would presumably be safer,” Harper said. “Savvy law enforcement officials were known to transport prisoners to jails in nearby … counties where they would be safer if they suspected mob violence.”

The second time Duncan and Coker were taken into custody and placed in jail, there were already other inmates in that jail. Among the other inmates were two young Black men, William Allen and Buss Kane. They had been arrested under suspicion of murdering an elderly white Civil War veteran.

“Over the next few hours, word circulates, a mob forms and it grows,” Harper said. “The mob goes to the jail, and the sheriff at that time puts up a very tepid response. … Before long, they break into the jail, and they drag out whoever they can get their hands on.”

The mob grabbed Duncan, Coker and Allen out of jail and took them to Drury College, which became Drury University in 2000. However, a crowd of Drury students encouraged the mob to lynch the men on the square, as it would look bad for the college’s image if a lynching took place on their property. The mob then moved to Park Central Square.

“After being tortured, they were hanged from Gottfried Tower,” Harper said. “The tower was topped by a replica of the Statue of Liberty. After they were lynched, their bodies were burned, and then desecrated in front of a crowd of thousands of men, women and children.”

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly how much the lynchings affected the demographics, politics and economy of Springfield. The Black population shrank to six percent by 1910, only four years after the lynchings. However, it is confirmed that the majority of African Americans either stayed or moved back to Springfield. This may have been due to the fact that Black workers played a major role in Springfield’s economy.

“Because of segregation, Blacks lived in their own community parallel to the white community in Springfield,” Harper said. “They had their own professional class: physicians, attorneys, teachers. There were Black-owned businesses like Hardrick Brothers Grocery, which was one of the largest grocery distributors in the area. The Black working class worked as day laborers, laundresses, hostlers, cooks and servants.”

These were jobs that did not appeal to the white population. This ensured that even after the lynchings and fear that spread across the community, Black people still had a way to earn income.

Though the majority of African Americans stayed, they did lose their political power as local Republicans no longer needed Black votes to win elections. Harper said that Lily-White Republicanism, a conservative movement in the Republican Party that emerged in the South, also sought to push Blacks out of the party at this time.

“After this, Blacks lose whatever little political power they had at that point and you don’t see Blacks in city government again in Springfield until the end of the 20th century,” Harper said.

It took until 2001 for Springfield to elect its first Black councilman, Denny Whayne, after the lynchings took place. Whayne was the former Springfield president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People from 1980 to 1988. Some look at Whayne’s success as a step in the right direction and have continued on his legacy towards inclusion. One such group is the Black United Independent Collegiate at Drury University.

“There are community organizations like the local NAACP chapter, GLO center and Grupo Latinoamericano, that work diligently to provide a supportive community for peoples coming from diverse backgrounds,” senior at Drury University and the President of the BUIC Serenity Sosa said. “At Drury University, we have many student groups cropping up like United Asian Voices, Sociedad de Orgullo Latino and a College Democrats chapter that all seek to foster community with like-minded individuals.”

Sosa said that if the words diversity, equity and inclusion make one feel apprehensive, then one should examine the quality of their life.

“Many of these traditional beliefs are hard to give up as they seem core to our identities,” Sosa said. “But it is also important to keep in mind that we have progressed past a climate of indignity. We are more than what we think, and there is no perfect image of allyship. To promote diversity in our community, we should share our thoughts and be open to different viewpoints that might challenge our deeply-held beliefs.”